Sometimes you just get lucky. That is the only way I can explain one of those rare, unplanned opportunities, which help make a career a little more compelling than the humdrum routine of a manager’s daily life. My good fortune occurred during my tenure as the executive director for the Minnesota Transportation Museum. And it was because I had accepted that position the year before that I received a phone call in 2001 from an acquaintance of mine, a celebrated railroad artist, who wanted to donate some of his artwork to the museum.

It was extremely easy for me to say yes without any hesitation even though I was initially confused about why the offer was being made. This call was, after all, from my favorite of all the then aspiring painters who drew their inspiration from rail related themes, and I wasn’t about to turn him away because of my own skepticism about his largesse.

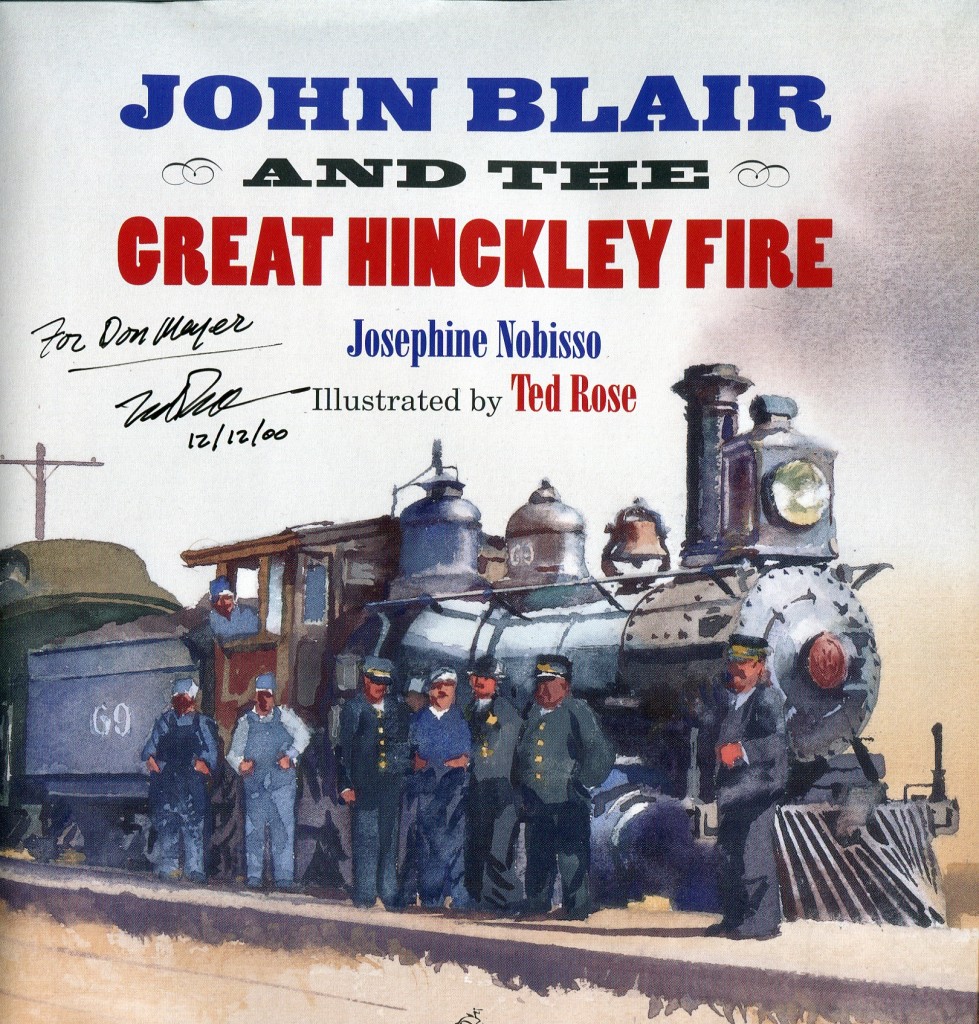

You would have had to have known Ted Rose to understand my doubt. He was not an easy man to get along with and his reputation as an artist was not built on any glimmer of a charitable spirit. He was well known as a water colorist, had a large client list, and could be the crown prince of artistic curmudgeons when you said or did something he regarded as being lame or, even worse, stupid. Most important of all, he was not to be questioned when he made a suggestion about the display of his artwork. But I felt lucky, once again, to have the opportunity to run the risk of offending his visionary sensibilities.

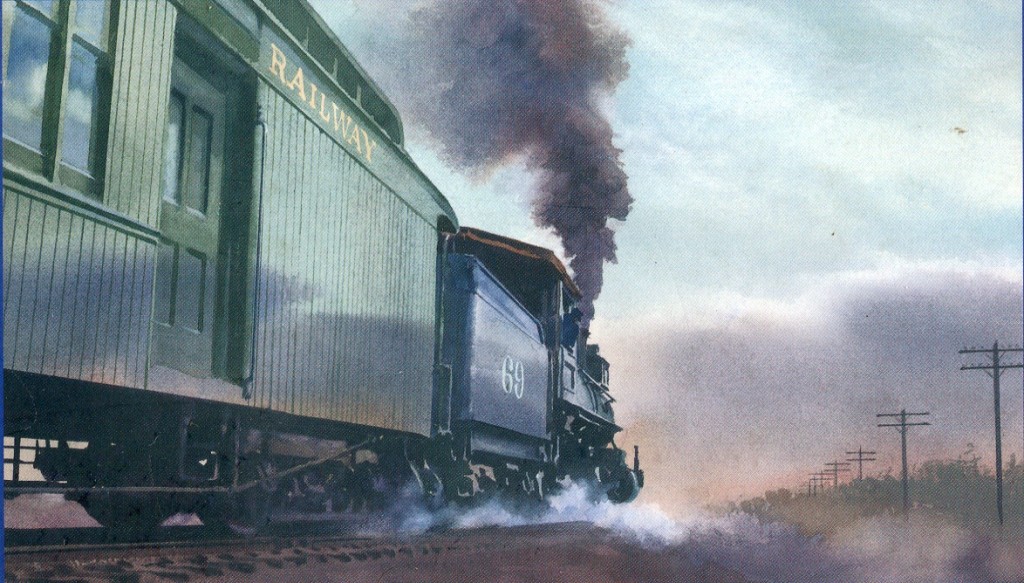

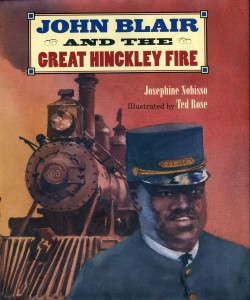

The occasion was his recent creation of a series of paintings to illustrate a children’s book about a rather horrific and historic incident known as the Great Hinckley Fire. More specifically the focus of the story was the deeds of an African-American porter for the Saint Paul & Duluth Railway by the name of John Blair. The year was 1894 when a monstrous firestorm engulfed the region surrounding Hinckley, Minnesota, where the dry accumulation of debris from the logging industry provided the fuel that became the source for the devastating conflagration.

The occasion was his recent creation of a series of paintings to illustrate a children’s book about a rather horrific and historic incident known as the Great Hinckley Fire. More specifically the focus of the story was the deeds of an African-American porter for the Saint Paul & Duluth Railway by the name of John Blair. The year was 1894 when a monstrous firestorm engulfed the region surrounding Hinckley, Minnesota, where the dry accumulation of debris from the logging industry provided the fuel that became the source for the devastating conflagration.

If you have never heard of this event, you are not alone. When Ted called to talk to me about it, I feigned a fabricated awareness in order to disguise my ignorance. I knew about the Chicago Fire that had decimated a fair amount of that city several years prior to Hinckley. But that was only due to the fact that it was the topic of a Tyrone Power movie I had once seen on television. And thus far the Great Hinckley Fire had failed to attract the attention of any Hollywood producers, directors or screenwriters, even though this particular catastrophe was of such epic proportions as to qualify as another Steven Spielberg blockbuster.

For me, however, the offer of the paintings proved to be the proverbial perfect storm for staging a museum exhibition in a museum lacking such rudimentary aspects of a truly cultural asset for the benefit of the local community. It combined the artwork of a prestigious contemporary painter, the compelling story of an important historic event for the region we were in, and the rare opportunity to showcase the positive role of African-Americans in early railroad operations. The importance of this last point was magnified by the location of MTM’s railroad museum, the former Great Northern roundhouse in St Paul. The location was strategically located to the north of what had once been the vibrant Rondo neighborhood, a black community that was obliterated to make way for I-94 to pass through the Twin Cities. We were about to make amends, however meager the result.

For me, however, the offer of the paintings proved to be the proverbial perfect storm for staging a museum exhibition in a museum lacking such rudimentary aspects of a truly cultural asset for the benefit of the local community. It combined the artwork of a prestigious contemporary painter, the compelling story of an important historic event for the region we were in, and the rare opportunity to showcase the positive role of African-Americans in early railroad operations. The importance of this last point was magnified by the location of MTM’s railroad museum, the former Great Northern roundhouse in St Paul. The location was strategically located to the north of what had once been the vibrant Rondo neighborhood, a black community that was obliterated to make way for I-94 to pass through the Twin Cities. We were about to make amends, however meager the result.

More elements that coalesced in this project to help make it a creditable experience was my acquaintance with a director for the Pan African Community Endowment Fund administered by the St Paul Foundation, who directed a fair portion of the Fund’s money towards the project as an exhibit sponsor. And I had a colleague on MTM’s staff who shared my passion for breaking out of the routine of our daily jobs to make something beautiful happen.

Much of the credit for the exhibition of the Ted Rose artwork illustrating the bravery of railroad porter John Blair goes to Wanda Sims. She was the project director for the renovation of the Great Northern roundhouse into a viable museum destination and welcomed the chance to help put something inside the structure that would lend credibility to the claim that this was, indeed, a history museum. It was through her contacts that we were able to assemble the rest of the financial backing needed to cover the cost of the exhibit and the opening reception. And together we enticed the participation of knowledgeable people from other museums, historical societies and the University of Minnesota to serve on our exhibition committee, allowing a business manager and a construction superintendent to make use of others’ expertise in achieving what we were not exactly trained to do.

The opening reception was by invitation only, consisting of a guest list that included in equal parts prospective donors I had been courting during my brief tenure as MTM’s executive director and donors to the Pan African Community Endowment Fund. Most of these folks had never set foot on any of the MTM properties. This was a groundbreaking experience for me as well as the organization I served, which puts me in mind of a comment I almost made when asked by an MTM board member during our preparations what kind of people would be attending the reception. I thwarted my cynical self’s ambition to say “black people” and opted for the more benign reference to “people of substance.” But in truth, when the doors to the roundhouse opened to welcome our guests to a most elegant setting inside an industrial structure, I was pleased to see the mixed ethnic composition and gloated (internally) at the compliments we received for the statement we were making about our role in bringing to light a hidden gem of railroad history, the powerful contribution of the African-American community.

The one sad note to this whole episode was the inability of Ted Rose to attend and share in the accolades of this wonderful event his gift generated. I was to learn a short time later through a mutual friend that Ted was dying of cancer. And the following year he was gone.

Ted was an obstinately unique fellow. He found beauty in industrial landscapes, favored the railroads whose imagery and history we both sought to popularize with the general public, and eschewed any attempt by anyone at fawning admiration of his talents. He remains my favorite railroad artist and I would encourage anyone who is curious about sampling some of his work to search the internet for Ted Rose artist. There you may get a glimpse of the genius behind the ornery personality that helped infuse my career with a moment of glory as sonorous as the colors of his artistic palette.