Most of my management career has involved transportation of the nostalgic kind, typically as the general manager or executive director of a rail-themed museum. The proof is in my collection of prized achievements represented in this web site’s Archives page. They bear witness to the fact that my name and reputation is little known outside of that small enclave of enthusiasts, who attempt to preserve the heritage of America’s railways in their spare time.

There have been a few blessed departures from the norm that have allowed me to pursue my broader interests in history before returning to a more stable method of occupational therapy, aka a job, where I have made a reasonably decent living. One of these departures was the opportunity to devise a fund raising plan for the repair of the Frank Lloyd Wright designed Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church in Wauwatosa, WI. And this week’s message relies heavily on the case statement I prepared for its members in order to tell the story of my own fascination with a campaign to repair something of greater celebrity than anything I had ever worked on before.

My knowledge of Wright was limited and my awareness of the Greek Orthodox faith and the prominent facility Wright designed for this Milwaukee based congregation was even less. Fortunately a host of background material was readily available, most prominently in the form of John Gurda’s book New World Odyssey: Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church and Frank Lloyd Wright.

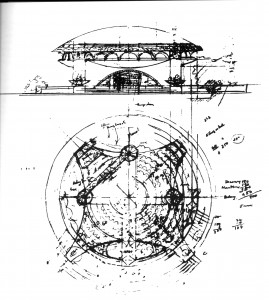

What I learned from this and other sources is that near the end of Wright’s career he accepted a commission to design a new worship facility for the members of this devout, ethnic community. It struck me as being an interesting collaboration between a man, whose vision and innovative talents transformed our perception of physical structures, and a people of faith, whose vision was for an internal transformation of heart and soul.

Wright drew on elements of Greek orthodox history to conceive of a structure resembling a Byzantine church molded from modern Midwestern materials and placed in an affluent suburban landscape. But Wright did not live to see his vision take form. He died in 1959 prior to the groundbreaking ceremonies that launched the construction of this fabled building, which eventually gained the stature of other famous Wright designs by being listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Wesley Peters, the first apprentice Wright ever hired for his Taliesin Fellowship, took over as chief architect for the church project. John Ottenheimer, a fellow architect whose role at Taliesin included serving as the entity’s archivist, preserving all of the documents, plans and drawings created by Wright and his colleagues, served as the on-site architect to insure the faithful implementation of Wright’s vision. And it was directly from John that I was able to learn about the issues related to the building’s initial construction and the subsequent need to repair one of its signature features.

Wesley Peters, the first apprentice Wright ever hired for his Taliesin Fellowship, took over as chief architect for the church project. John Ottenheimer, a fellow architect whose role at Taliesin included serving as the entity’s archivist, preserving all of the documents, plans and drawings created by Wright and his colleagues, served as the on-site architect to insure the faithful implementation of Wright’s vision. And it was directly from John that I was able to learn about the issues related to the building’s initial construction and the subsequent need to repair one of its signature features.

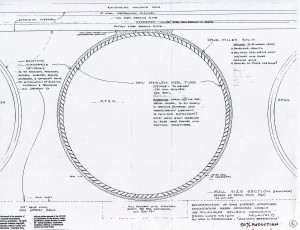

Wright’s design was essentially that of a circular structure with a domed roof. The section of exterior wall immediately below the roof was called the dome support band. It was to be comprised of 261 solid glass units set into the concrete wall. It was an attractive feature meant to allow the ambient light to filter into the church’s interior, but it proved not to be either feasible or affordable. Instead a hand blown, hollow glass alternative was manufactured and inserted into the wall between pairs of steel rods, installed to provide the necessary structural support.

At the time of construction the prevailing attitude among the Taliesin staff was that this type of fix would need to be corrected at a later date. This was affirmed in a 1974 report from Ottenheimer to Peters following a visual inspection of the facility. Clearly visible to him at that time was the accumulation of water inside some of the hollow glass spheres, for which he identified three causes: the extreme seasonal changes in the exterior temperature, the lack of proper humidity control inside the facility and the “… limitation of technology and budget at the time of construction.”

By the time I got involved another forty years had gone by and the need to take corrective action was even more apparent. Approximately 50 of the hollow glass spheres were noticeably cracked, trapping moisture inside the units, corroding the steel support rods and eroding the concrete walls.

Of all the principals from the Taliesin Fellowship who were involved in the construction of the church, John Ottenheimer was the sole survivor. His concern for the structure was still palpable during our conversations and e-mails. And it was during these exchanges that I learned about his passion for perfecting a viable solution that would also provide a desired continuity with Wright’s original vision.

Ottenheimer’s proposed remedy was to replace all of the 261 hollow glass spheres with stainless steel cylinders, having the same 12” diameter and inserted into the gaps created as each sphere was removed. Convex glass lenses, capable of withstanding the seasonal changes in temperature, would then be affixed to each end of each steel tube forming a glazing unit, which, when properly sealed, would prevent further water damage from taking place. This innovative, though untested design, would also add strength to the dome support band should any of the original steel rods fail.

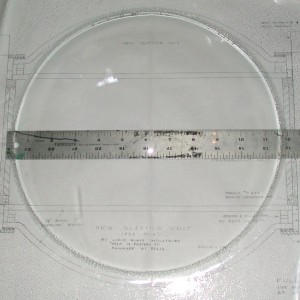

Manufacturing the cylinders would be the easy part. The 522 lenses needed to cover both ends of the 261 cylinders in the dome support band would prove to be the most vexing part of the operation if it were to succeed. And the person on hand with the skills to craft these exquisite elements was someone who had proven her worth to me in a previous collaboration, the restoration of the Badger No. 2 fish-stocking railroad car for the Mid-Continent Railway Museum. Catherine Lottes, owner of Lucid Glass in Milwaukee, was highly experienced in the manufacture of specialty glass items and the plan was for her to create the prototypes for the lenses during a proof of concept phase, which would allow the design to be refined, if necessary, before production would begin on the remainder of the lenses.

The best estimate for the design, manufacture and installation of the completed glazing units was $550,000. I rounded this up to an even $600,000 based on my experience that the best laid plans of mice, architects and engineers always exceed budget. To raise such a sum was beyond the means of the small congregation alone and that meant opening up the fund raising campaign to encourage gifts from outside sources capable of making significant contributions. And this posed a different kind of problem.

People are reluctant to give to a religious organization for fear that their money will be used to promote a group’s sectarian doctrine. To mitigate this impression we set up a fund to be administered by the Greater Milwaukee Foundation for the singular purpose of paying for the building’s repair and maintenance. This step was intended to assure every donor, who wanted to repair and stabilize a Frank Lloyd Wright building, that the funds would remain independent of any religious programing. But it was important to me that the fund retain its identity with the Greek orthodox tradition and here is where my own creative instincts – or maybe cleverness – kicked in to merge the sacred with the profane to give the campaign its dual personality.

In classical Greek the word kairos was used to indicate a moment in time when a decision had to be made to insure an idea’s success. It was in fact considered to be the supreme moment for a person to act. And it was taught by the philosophers that a truly informed person “rarely misses the expedient course of action.” Similarly in the orthodox tradition there is a moment before the Divine Liturgy begins when a deacon whispers to the priest, Kairos tou poiesai to Kyrio, “It is the supreme moment for the Lord to act.”

It was easy for me, then, to christen the fund being held by the Greater Milwaukee Foundation The Kairos Fund in recognition that this was to be the supreme moment to take action in order to protect the structural integrity of a building that united Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision with the sensitivities of the orthodox community. My hope was that people would perceive the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church to be a place of worship as well as a cultural asset. Unfortunately, it was not to be. I failed to bring the most important step in this project to closure, the acceptance of the congregation to take on the full responsibility for the campaign’s ultimate success. And so my own supreme moment in time came to an inglorious end. The restoration of a 1907 steam locomotive awaited my willing though meager talents.

The whole episode did allow me to develop a better appreciation for the career that I have pursued in historic preservation by renewing my faith in why we do what we do. Spiritual values may be eternal but all physical structures, whether designed by the best architects or we mere mortals, are subject to deterioration and can only survive through proper care and the immediate remediation of serious defects. Wright’s celebrity was not enough to make his designs immune to the inevitability of decay with the result that of the 400-plus Wright designs that were actually constructed nearly one-fourth have subsequently been demolished, their brief moment in time all but forgotten.